When preparing a paediatric investigation plan application, an experienced medical writer should be on hand to help interpret the requirements of the guideline.

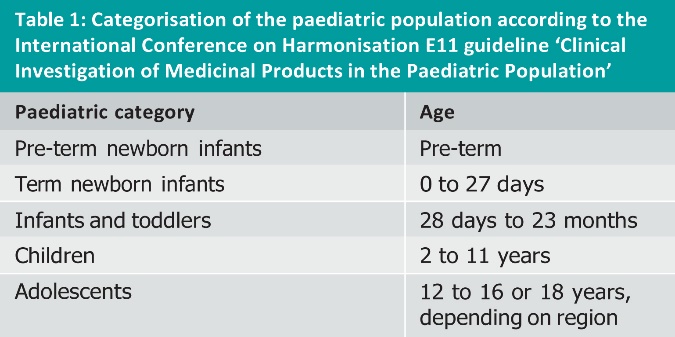

The paediatric investigation plan (PIP) application is a recent addition to the line-up of European regulatory requirements that confront the pharmaceutical industry. It is the culmination of years of concern from regulators that most drugs are approved with little or no evidence of their efficacy and safety in the paediatric population. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) believes that “50 to 90 percent of paediatric medicines have not been tested and evaluated” [1]. Even a brief search of the internet provides evidence of the often tragic consequences associated with the inappropriate treatment of children with drugs tested in adults. In addition to ethical concerns about conducting clinical studies in children and a frequent lack of commercial interest from pharmaceutical companies, there are many practical difficulties in conducting paediatric clinical studies. A further challenge is that the paediatric population is far more diverse than the adult population, ranging from preterm neonates to adolescents (see Table 1), and there may be substantial differences in the way a drug performs between these different age categories. In this respect, there is now increasing sensitivity to the fact that the paediatric population should not be treated by simply reducing the recommended adult dosage.

Since enforcement of the Paediatric Regulation in 2007 [2], sponsors must possess a compliant PIP when applying for marketing approval of unauthorised drugs, or when applying for approval of new indications, pharmaceutical forms, or routes of administration for currently authorised drugs. The default situation is that a Marketing Authorisation Application (MAA) should now include findings from the paediatric population that were obtained in clinical studies designed and conducted according to measures described in a PIP that was agreed upon beforehand by the EMA’s Paediatric Committee (PDCO). The Paediatric Regulation also stipulates that an MAA should not be delayed on account of the paediatric development, thus there are also provisions for deferring or waiving some or all paediatric measures, as this article will outline.

The core deliverable for a PIP application is the “scientific part of the application”, which is a document structured according to the EMA’s PIP guideline [3]. A length of “below 50 pages” is recommended, which can lead sponsors preparing a PIP for the first time to underestimate the time and effort required. Although regulatory personnel may be well versed with the paediatric regulations, it is often the professional medical writer with hands-on experience of preparing PIPs through to production of the final, submission-ready deliverable who can guide the sponsor’s team through the practical complexities of understanding which information needs to be included where, and how to obtain and present it.

With this in mind, and assuming the need for a PIP has been established, there are six main steps involved in preparing a PIP application:

- Consult the guideline and associated resources

- Plan resources and timelines

- Summarise information on the drug and the intended indication

- Position the drug in the spectrum of therapeutic options

- Provide a convincing rationale for the paediatric strategy

- Complete the PIP package

An experienced medical writer should be involved in all these steps. For teams that are often contributing to a PIP for the first time, a medical writer brings a wealth of experience and can be crucial to ensuring cross-functional consistency of content throughout the process.

CONSULT THE GUIDELINE & ASSOCIATED RESOURCES

The final guideline on the structure and content of the PIP was published in September 2008. At first sight this is not a particularly user friendly document. For example, it often refers to specific articles of the Paediatric Regulation that themselves are sometimes challenging to interpret. Fortunately, the EMA’s website provides a number of other sources of information that can help in preparing a PIP. Foremost among these are the electronic form for the paediatric investigation plan application and request for waiver (a PDF file sometimes referred to as the ‘PIP template’), and the EMA/PDCO summary report template with internal guidance text.

One misconception is that the PDF file is a template for the entire PIP application (including the ‘scientific part of the application’ in parts B to F). This is not the case. Instead, this file is a dynamic PDF form that covers part A of the PIP application. It addresses administrative aspects such as details of the applicant, the drug, the intended indication, and so on. However, at the end of the form is a table of contents that provides the recommended structure for the scientific part of the application (see Table 2). This content should be written in a separate Word file. Confusingly, the suggested structure is not identical to the organisation provided in the final PIP guideline, but fortunately the difference lies only in the order in which information is provided.

Thus, based on the table of contents given in the PDF file, applicants can create their own templates in a Word file for writing parts B to F of the application. Table 2 shows the high level structure suggested by the EMA, which in practice will be augmented with subsections that can be tailored to the specifics of the application.

The EMA/PDCO summary report template is used for writing an assessment report that enables the PDCO to review the application. The template is helpful for applicants because it provides recommendations on what reviewers should assess and comment on. Thus, by addressing these issues during authoring of the PIP, the writer can tailor the PIP’s content to the PDCO’s expectations and reduce the number of issues arising during review.

PLAN RESOURCES & TIMELINES

As with other regulatory documents, realistic planning of resources and timelines is crucial to the timely success of preparing the PIP. An almost hard and fast rule is that writing a PIP requires more resources and time than initially estimated by the applicant. This can be partly due to a lack of experience, and partly because PIPs often need to include substantial amounts of text drafted anew rather than being adapted from existing material. As this article goes on to explain, such texts include background information on the paediatric population and the disease at hand (which can be difficult to obtain), along with the rationale for the measures that constitute the paediatric development strategy (which can involve lengthy discussions and multiple revisions).

The resources required will depend on the applicant company’s size and structure. In general, the core team should include at least a regulatory coordinator and an experienced medical writer, together with representatives from the CMC, non-clinical and clinical functions, and (if applicable and available) a publisher to compile the submission package. While the functions may contribute the necessary materials for their subject areas, including texts that can be ‘just added to the document’, such texts do invariably need to be worked upon to fit in with the rest of the document. Experience has shown that the medical writer’s input is invaluable in ensuring consistency of content between the different sections. The medical writer’s oversight is also essential as a means of maintaining an overview of the material still required along with the date it will be needed by if the envisaged submission date is to be met.

The submission date for the PIP application will usually be linked to one of the monthly PDCO meetings in the overall context of the anticipated date for the MAA submission, by which time a compliant PIP is required. Working back from the MAA submission, it is prudent to think ahead about issues that will need to be addressed after initial submission of the PIP. Realistically, it can take at least six months between submitting the PIP and obtaining agreement on the paediatric measures contained therein. The time taken to prepare the PIP will depend on the amount of dedicated resources available and the extent of information to be included. Even when a project is well-resourced, considering the time needed for literature searches, obtaining advice on paediatric strategy, authoring, at least two rounds of review, finalisation and compilation (including annexes in part F), a timeframe of at least five months is realistic for preparing a submission-ready PIP. Thus, the time between starting to prepare a PIP and obtaining agreement from the PDCO can easily extend to a year.

SUMMARISE INFORMATION ON THE DRUG & THE INTENDED INDICATION

In part B, the applicant has to provide background information to support the rationale for the proposed paediatric strategy described later on in parts C and D. The most challenging part to write is generally part B.1, which provides information on the disease to be treated and the expected performance of the drug (or class of drug). Specifically, the guideline stipulates information on known and expected similarities and differences between adults and paediatric subjects, and between different age categories within the paediatric population. Topics to be covered include characteristics and seriousness of the disease, prognosis, epidemiology, the drug’s pharmacological properties and mechanism of action, and known or expected safety and/or efficacy information related to the mechanism of action. Safety and efficacy data from clinical trials in adults should not be summarised here, but in part D instead.

Bearing in mind that the paediatric population is highly diverse, it is often difficult to obtain the necessary information for part B.1 to cover all age categories (see Table 1). In terms of disease characteristics and epidemiology, a literature search is often required, which can be time-consuming and expensive. At kick-off meetings for PIPs, it is not unusual for medical writers to be confronted with statements such as “all the information is available in the investigator’s brochure”, which will rarely, if ever, be the case. The medical writer is therefore often left needing to educate the team about this important section, the purpose it serves, and, depending on the indication involved, the often considerable effort needed to research the relevant information and summarise it at the appropriate level for a PIP.

POSITION THE DRUG IN THE SPECTRUM OF THERAPEUTIC OPTIONS

In part B.2, a review of current methods of diagnosis, prevention and treatment in paediatric populations for the disease at hand is required. Again, this section might require some literature research as well as consultation of regulatory information and drug approvals, as available on the internet. The key elements to be summarised include current treatments and standard of care options across the entire paediatric population, along with how the applicant’s drug differs from these options. If applicable, information in this section would also be used to justify the options for active comparators in the proposed clinical studies.

Against the background of the information in parts B.1 and B.2, the applicant has to provide a justification in part B.3 for the anticipated therapeutic benefit of the drug. The key questions here are whether the drug is expected to provide improved safety and/or efficacy compared to current therapeutic options in some or all of the paediatric population, or whether comparable efficacy and/or safety are expected but with an improvement in quality of life due to, for example, an improved dosing regimen or an age-appropriate mode of administration.

PROVIDE A CONVINCING RATIONALE FOR THE PAEDIATRIC STRATEGY

Supported by the considerations in part B, the applicant will need to set out a clear paediatric strategy that is acceptable to the PDCO. A primary aim of the Paediatric Regulation is that clinical studies should be designed and conducted to provide paediatric data that can be used as the basis for the drug’s prescribing recommendations. However, depending on the type of drug, the nature of the disease and the epidemiology of the disease across the paediatric population (as described in part B), the applicant may instead decide upon a strategy that includes proposing a waiver and/or a deferral for measures in some or all of the paediatric population. A waiver means that the applicant proposes not to conduct paediatric measures. A deferral means that paediatric measures, including clinical studies, are proposed but that their completion and reporting are to be delayed until efficacy and safety have been demonstrated in an MAA submission for the adult population.

In some cases a class waiver (in other words, a waiver for the class of drug) may be applicable, and the applicant can refer to this in the rationale for not conducting paediatric studies in some or all age categories. This does not absolve the applicant from submitting a PIP, even if a class waiver covers all age categories. Class waivers published by the EMA are typically available for drugs used to treat diseases occurring only in adults, or where there is reason to believe that the class of drug is unlikely to have adequate efficacy or safety in paediatric patients. In addition, product specific decisions published by the EMA may also provide insight from similar types of drugs as to whether a waiver may be appropriate for the applicant’s drug. Waivers will only be granted by the PDCO when the applicant can make a convincing case that paediatric measures are not warranted. An applicant’s lack of interest in conducting a development programme for all or some of the paediatric population is not an acceptable reason for proposing a waiver.

The application for a deferral is product specific and is generally driven by practical considerations such as availability of an age-appropriate formulation of the drug, the need for further nonclinical studies, or the requirements of a global clinical development strategy (for example, driven by the availability of data from other regions).

A common situation is that the applicant proposes paediatric measures for at least part of the paediatric population, and a waiver for the remainder. For the writer the challenge is to craft a convincing rationale for the design of these measures that harmonises with the background information provided in part B. This is not a trivial point; there is often an inherent tendency by applicants to propose a minimal number of measures, and such an approach may be difficult to align with the information provided in part B and may also contradict the PDCO’s somewhat academic approach to the need for paediatric measures. The result is that rationales for waivers (in part C) and proposed paediatric measures (in part D) usually result in a high degree of iteration between the medical writer and other team members over a period of several weeks before the texts are agreed upon by all. To a lesser extent the same is also true for the rationale for a deferral provided in part E.

In part D of the PIP, which is the core of the ‘plan’ being proposed, the descriptions of the paediatric measures to be conducted are preceded by summaries of existing information relevant to the drug’s formulation and its nonclinical and clinical development. In terms of clinical development, this section should provide an overview of existing data on the efficacy and safety of the drug obtained in clinical studies in adults. However, clinical pharmacology data should not be provided here because this information will already have been summarised in part B in the context of the drug’s pharmacological properties and mechanism of action. If necessary, cross-references may be used back to information summarised in part B.

The paediatric measures being proposed, in terms of ‘quality’ (for example, in the development of an age-appropriate formulation) and nonclinical as well as clinical studies, need to be specific in terms of strategy, method descriptions and timelines (the EMA provides a PDF template for synopses of nonclinical and clinical studies). Here, the writer is often confronted with the team’s desire to be as noncommittal as possible, but anecdotal evidence consistently suggests that the PDCO requires specific descriptions of measures that may be conducted several years in the future, including details of statistical analyses. Furthermore, the timelines for all proposed measures need to be specified in relation to the submission date for the MAA. The timelines have to be defined to at least the nearest quarter year and are binding; once an agreement on the PIP has been obtained, they may only be changed via the laborious procedure of a PIP amendment. The details of the paediatric measures and their timelines are usually the subject of intense discussion within the team, and the writer can play an important role in ensuring that the measures are aligned across different functional areas and in the overall context of the background information on the drug and the disease presented in part B.

COMPLETE THE PIP PACKAGE

Even after the team has reached agreement on the content of parts B to E, time should be allocated to complete the PIP package through to submission readiness. This is the time when the content is now stable and the writer can finalise technical issues such as formatting, cross-referencing, and ensuring consistency of language. There are also a number of technical requirements specified by the EMA that need to be taken care of, such as removing active hyperlinks to references or tables and figures, and listing alphabetically the references to published literature at the end of the PIP [4].

The annexes in part F will also need to be completed during this time. In addition to providing copies of all published literature referred to in parts B to E, the annexes should also include other relevant reference materials where available, such as an investigator’s brochure, a risk management plan, product information if the drug is already approved, any opinions and/or decisions received for the drug from regulatory authorities, and any official scientific advice received on the drug. Although the annexes should ideally be compiled as far as possible while the PIP texts are being drafted, in practice a large part of this task is often completed shortly before submission and careful planning is needed to avoid this becoming a rate-limiting step. The services of a publisher are required for electronic compilation of a PIP submission, and in practice the medical writer also acts as an interface between the publisher and the rest of the team for resolving last-minute issues before the PIP application is ready for submission.

CONCLUSION

The PIP is a relatively new type of regulatory submission document that many applicants still have little or no experience of preparing. Depending on the drug and the disease at hand, the PIP can be a demanding document to write and the effort required in its preparation is often underestimated. An experienced medical writer can play a key role in helping applicants interpret the requirements of the PIP guideline so that team members can provide the required material and scientific guidance needed for writing the various sections of the PIP. Ultimately, by interacting proactively with the applicant’s team, the medical writer’s goal should be to ensure that the PIP is as clear and focused as possible so that only a minimal number of issues for resolution are raised during its review by the PDCO.

REFERENCES

- European Medicines Agency, Presentation on the Paediatric Regulation by the Paediatric Team, Scientific Advice, Paediatrics & Orphan Drugs Sector, EMA 2007, www.emea.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Presentation/2009/10/WC500004243.pdf

- European Medicines Agency, The Paediatric Regulation, www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/regulation/document_listing/document_listing_000068.jsp&murl=menus/regulations/regulations.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac0580025b8b&jsenabled=true

- European Medicines Agency, Guideline on the format and content of applications for agreement or modification of a paediatric investigation plan, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:C:2008:243:0001:0012:EN:PDF

- European Medicines Agency, Q&A: Paediatric Investigation Plan (PIP) guidance, www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/regulation/q_and_a/q_and_a_detail_000015.jsp&murl=menus/regulations/regulations.jsp&mid= WC0b01ac0580025b8e

Douglas Fiebig

Published in: International Clinical Trials, May 2011